Thinking outside the box

My first startup involved revolutionizing exterior accessories for Jeep. While I didn’t realize it at the time, we created a startup org within FCA from the ground up, based entirely on unsolved customer pain points. As with any good startup, great ideas stem from novel solutions to problems customers experience every day. At Jeep, one of the biggest customer pain points was buying a vehicle capable of an open air experience, but not being able to take advantage of it due to difficulty with storing the removed top. AND once the top was off, heaven forbid you encounter bad weather. Difficulty and anxiety are not key Jeep brand traits and as a Jeep enthusiast, this is a problem that has plagued me personally along with countless friends, family, and acquaintances.

Timing is everything

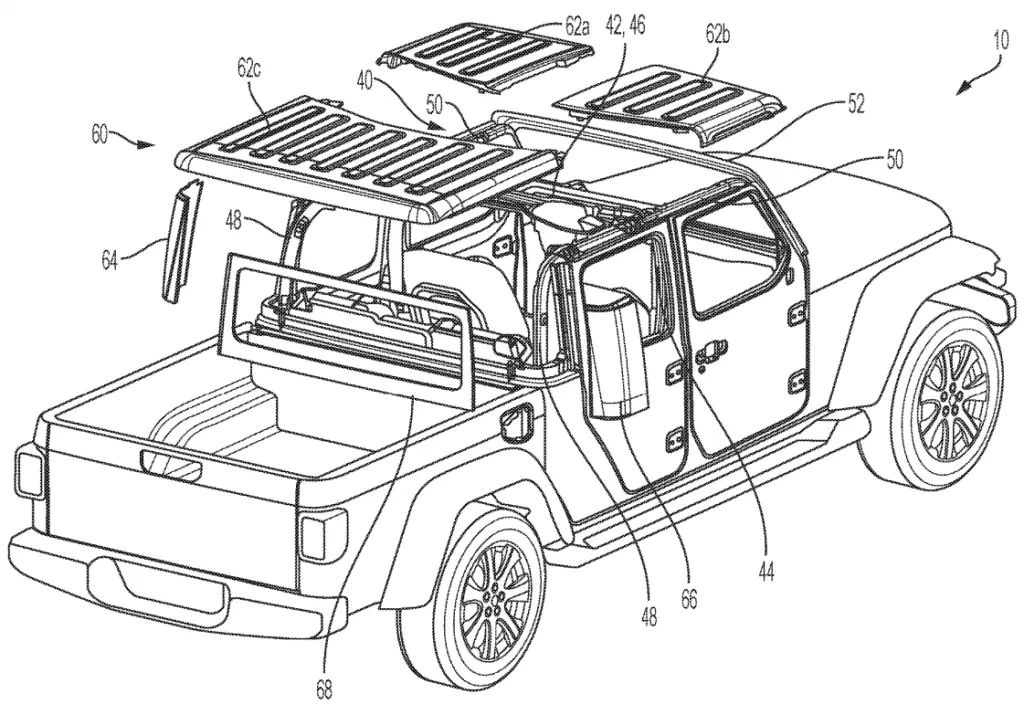

The Jeep Gladiator launched in 2018 and while sales started strong, by 2020 momentum was starting to slow. The Gladiator was the most expensive vehicle in the burgeoning midsize truck segment, offering class-leading off-road capability with a class-exclusive open-air driving experience. New segment entrants were on the horizon from Chevrolet, Ford, Toyota, and Honda, and the Gladiator while relatively new, needed to stake its claim.

Customer data indicated that the open air driving experience enabled by the removable roof was a key selling feature for the Gladiator, yet one of the key pain points identified was difficulty removing and storing the hard top roof. As any Jeep CJ, Wrangler, or Gladiator owner can attest, removing the hard top is a pain. Disconnecting, lifting, and storing the top is a multi-person and space intensive effort that really throws a wrench in the happy-go-lucky open air freedom that comes with buying a Jeep.

At an internal FCA townhall, the newly appointed COO gave a very motivating talk to employees around creative design thinking, pushing boundaries, and encouraging us to bring new ideas forward, directly to him if necessary. I specifically joined the Jeep brand to exercise this sort of thinking and was encouraged to have a like-minded high ranking official to report to. The hard top conundrum was at the top of my mind after that meeting, but I set off to continue my day job as the WL Grand Cherokee Product Manager.

The aha! Moment

My co-founder Rob and I enjoyed blowing off steam from our jobs in Jeep product planning by walking through the basement of the FCA HQ. It was like Willy Wonka’s Chocolate factory for car enthusiasts like us. Small vehicles with big engines, big vehicles with big lifts, test assembly lines with things we’d get fired for taking pictures of, it was a very exciting and thought provoking environment. We’d stroll the halls and invite ourselves into rooms we probably shouldn’t have been in, opining about what we’d do if we were in charge and what an incredible world FCA would be.

One day on one of these walks as we descended the escalator to the basement level, at the bottom was a new Gladiator kitted out with all the best Mopar accessories. The Gladiator was still relatively new at the time, and this was our first opportunity to get up close and personal with one. It was lifted with 37″ tires and Mopar beadlock wheels, Mopar bumpers with a Warn Zeon winch on the front, enough exterior lighting to rival the sun, and a painted body color hard top. We took a step back to take in the entire vehicle profile and bask in its glory when we saw it…is the roof of the truck the same length as the length of the bed? And if it is, could the top be stored on the bed and serve double duty as top storage and a tonneau cover?

We were infected by the idea, and set off to find a tape measure to prove the concept. We worked our way into a development area where we found two engineers working on wiring harness routing mockups. We approached and asked if they had a tape measure we could borrow. They did, but looked at us like we were crazy “sure, but what are you doing?” We took the tape measure and scanned the room to find a Gladiator disguised by disassembly across from their work station. “We’ll tell you in a second” we confirmed as we set straight for the truck.

First we measured the roof, then the bed, and the measurements were within an inch of each other. Rob and I looked at each other in awe…could it be this simple? We immediately started brainstorming when the two engineers came over to reclaim their tape measure and asked what we were excited about. “The top could fit on the bed!” we exclaimed, and as soon as they saw it, they were hooked. With nothing more than creative cutting, the top could be removed and stored on the truck bed, solving countless customer concerns and possibly making the Gladiator more appealing than the Wrangler for top storage.

nothing tells a story better than a prototype

Updating power point slides or running wire loom around firewalls gets tremendously boring day in and day out. The four of us immediately found common motivation to exercise our creative minds. We knew if we just took the idea to some form of leadership it wouldn’t go anywhere. “Too expensive”, “too hard”, “not possible” were common refrains from our planning leadership but this idea was one we were convinced would change the Jeep world and we were willing to put in the lunch time and after hours effort to turn it into reality.

A prototype is the foundation of a pitch, and we set forth building our prototype immediately, even just to prove the concept. We didn’t have a budget or official allocation for time, so we had to be resourceful. We needed a truck and a top. The truck we measured was allocated for scrap, so we worked with the shop manager to keep it from going to the scrap heap for a few months off the books claiming a request for research from “up high”. The top however, would be “destroyed” for our prototype and our truck didn’t have one.

On previous walks, we knew there was an area where vehicles that were used for crash testing were staged before being sent out for recycling. All parts on these vehicles needed to be destroyed for safety reasons, meaning if we found a crash tested Gladiator with a top, it would be destined for the recycling bin. We walked by the scrap area every day for two weeks until we found it, and Rob and I looked insane dressed in business casual clothes walking a cracked Gladiator top through the bowels of the FCA basement. Now, we had our materials.

We were careful with who we let into our idea circle. Collaboration is great when everyone is like minded, but a naysayer could throw a wrench in everything. As we started work on our prototype, it became clear that we needed some additional help, so we tapped our internal network to find a hardtop engineer and another fabricator. We became a team of 6 “JT6” as we’d call ourselves, the team that Jeep can use to solve big customer problems.

one concept spawns many with design thinking

We could have just hacked apart our newly acquired Gladiator top, ratchet strapped it to the bed, and called it a prototype. That’s where we started but it wasn’t the true solution to the customer problem…ease of removing and storing the hard top. We weren’t just developing a prototype, we were developing a user journey. By putting ourselves in the shoes of the customer, we thought through each step of the user journey for removing the top and placing it on the bed. We wanted something that considered every detail and truly surprised and delighted customers “they thought of everything” was our mantra in developing the prototype.

Removing the top:

- Remove front “freedom panels”

- Where do they go?

- Remove side quarter panels

- How?

- Where do they go?

- Remove rear window

- How?

- Where does it go?

- Remove rear of top

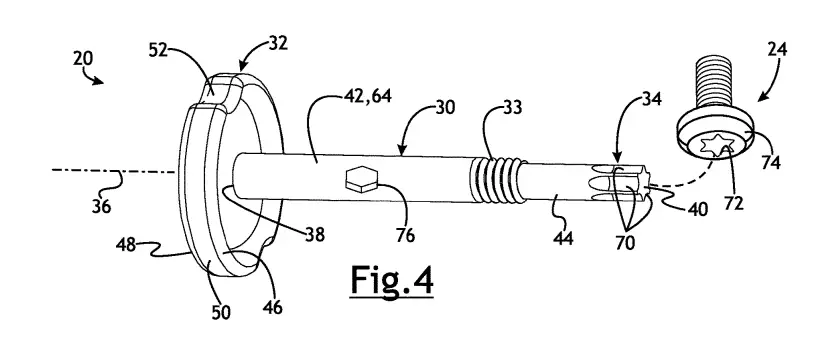

- Torx head bolts need to be removed and stored

Installing on Bed:

- Mount front “freedom panels”

- New frame required because freedom panels come off first and need to be put on the bed first but interface with the top last

- Mount rear of top to bed

- Using what fasteners?

By focusing on the customer and their journey, we identified a number of areas for innovation including another patent. Removing fasteners required separate tools and by examining and streamlining the workflow, we identified that we could use the removed faster as the tool! Not only does this reduce the need for more tools, but it reduces steps and simplifies the entire user process. reducing tools and steps required.

pitching - if at first you don't succeed, try try again

We had our prototype dialed in. Everything worked in the real world and it worked well. We were so excited and proud of what we accomplished we couldn’t wait to show the world. Chomping at the bit, Rob and I debated how we’d navigate the corporate political waters. We built something incredible off the books and almost entirely under the radar. We could really ruffle some feathers with what we’ve done, so applying strategy to who we pitched our product to was paramount. In our day jobs, we were responsible for planning new features for vehicles. There was a standard practice to follow (which we hadn’t so far), so as a good trial run, we decided to pitch in good faith to our immediate management.

Our pitch was so polished. A few slides to perfectly set up the customer problem, identifying market opportunity, then a flawless physical demonstration of the user journey. We practiced it countless times before bringing in a key stakeholder, and when we did…our direct boss, we were met with “oh, that’s neat. I gotta run”. Huh? This huge customer problem, our perfect solution, even a fantastic physical prototype! We were stunned, but not deterred. We pressed on, and his objection was “in this environment, we’ll never get the development cost past leadership.”

Leadership…that’s when we recalled the COO’s town hall speech around bringing good ideas forward, directly to him if necessary. So that’s what we did. Rob and I approached his admin requesting just 15 minutes for an “exciting new product feature demonstration”. Much to our surprise, she awarded us 30 minutes the next week. We continued practicing and refining both the pitch and the prototype and when the moment came, we were ready.

Mark Stewart was a lively exec, and openly expressed enthusiasm for our initiative even before we started the pitch. As a fellow “Jeep guy” he nodded aggressively through our entire pitch. Then came the prototype demonstration where we took a stock looking Gladiator and swapped the top to the bed. It went off without a hitch and Mark’s jaw was dropped the entire time. Eyes wide open like he had seen the greatest innovation in the company, he just responded with “Mike’s gotta see this…guys this is something incredible, I gotta run but I’ll have my admin reach out” and off he went.

Mike…as in Manley, the CEO? 30 minutes later, we got a message from Mike Manley’s admin asking us if we could “show him what we showed Mark at 7am the next week”. Absolutely!

Within 3 weeks of pitching our boss and getting a “meh” response, we were about to pitch the CEO of the company. Persistence paid off, and underscored an important lesson to never stop. We got in early to made sure everything was perfect. Mike came at 7am on the dot with an entourage. We had to guide him through the bowels of the basement to our secret work space, a place he had clearly spent very little time. We felt the underground somewhat grungy environment helped drive home the passion and grit of our team and the project.

“Show me what you got” he directed, and off we went. Another flawless pitch and demonstration, though unlike Mark, Mike was more stoic. Hard to read his impression until we fastened the final clamp on the top bed tonneau and he started the slow clap. “Bravo guys, outstanding work, get this in production…” and off he went.

Scaling an innovation team

Our prototype resulted in 6 separate patent applications, of which 2 were awarded and published (as shown above). The hardest work was yet to come, which is getting CAPEX allocated for development, ensuring positive unit economics, go to market planning, etc. Automotive is a long-lead development cycle meaning our top would take 2-3 years to develop. This first hurdle was taking our lumps with our direct management, who we needed to work with to productize our top. We skipped 3 levels of leadership by going directly to the COO, and while he was happy and encouraged it, it was obvious that we dinged our reputation with a few execs. We went on a roadshow, completing our pitch for every exec that felt slighted…more than 10 times over the next few weeks. It started to feel like our full time job, and that’s when it set in that we effectively created our own startup.

With the COO and CEO on our side, our pitches to other leaders went smoothly. Most were envious that they didn’t have the opportunity to take our idea for themselves, but all begrudgingly supportive of what they recognized was a great idea. The wheels for production were set in motion, leaving us without much new to do day to day. We were invited to a lunch in the executive lunchroom with Stewart, where he asked us to keep going. There were many product problems to solve, and he wanted us tackling more. How do we make the Wrangler top better? How do we make the Cherokee more desirable? What other wild opportunities could we identify?

We established weekly pitch touchpoints with the 6 of us, and quarterly touchpoints with leadership. Each week we’d sit with each other and pitch new ideas. The ones we all agreed on pursing would move to prototype phases. We had a Wrangler top concept, along with a pivoting light bar that became a Mopar accessory concept in 2024.

Most startups fail, ours included...kind of

It’s well known that most startups fail, and our was no exception…sort of. Our team was building tremendous momentum at the end of the 2019. Our pitches were going well, stakeholders were enthused, and planning for new model years was well underway. The timing was right, until it wasn’t. Two key events happened that derailed our progress…the FCA/PSA merger creating Stellantis and a little thing called COVID-19. Our last team meeting in the basement of the tech center occurred the last week of February 2020. We had been invited to join the Easter Jeep Safari in Moab, UT to witness more customer innovations first hand. We were excited, discussing travel plans and making preliminary arrangements. We left the building with enthusiasm off the charts, little did we know it would be the last time our team would be together in person in that building.

While the massive annual Moab event was cancelled that year, we continued work remotely. Our weekly meetings persisted and we started work on innovations for the Wrangler…one of which is the light bar above. Mark Stewart even had us share our story virtually during one of his town hall meetings, and things seemed like they were going in a positive direction. Unfortunately, the pressures of the major corporate merger started taking their toll, and investment in new innovations like ours were slashed. Our top was shelved and unlikely to see production due to high tooling and development costs, but we soldiered on with new innovations and pitches.

A few of us (including yours truly) found employment outside of the new Stellantis corporation due to lack of confidence in the company’s direction. The team soldiered on and inspired a new “intrapreneurial” initiative at Stellantis. That team has since grown and continues to innovate within the halls of the tech center. As with many first mover innovators, few will remember our JT6 team, our top, and what we accomplished in our brief time together. The patents with our names attached are lasting reminders of that rare time when the stars align between a great idea, immense talent and incredible passion tying it all together.